Mike Collins and Toby Greany summarise the themes they heard in interviews with educational leaders in Northern Ireland -Coast

Introducing Northern Ireland Coast

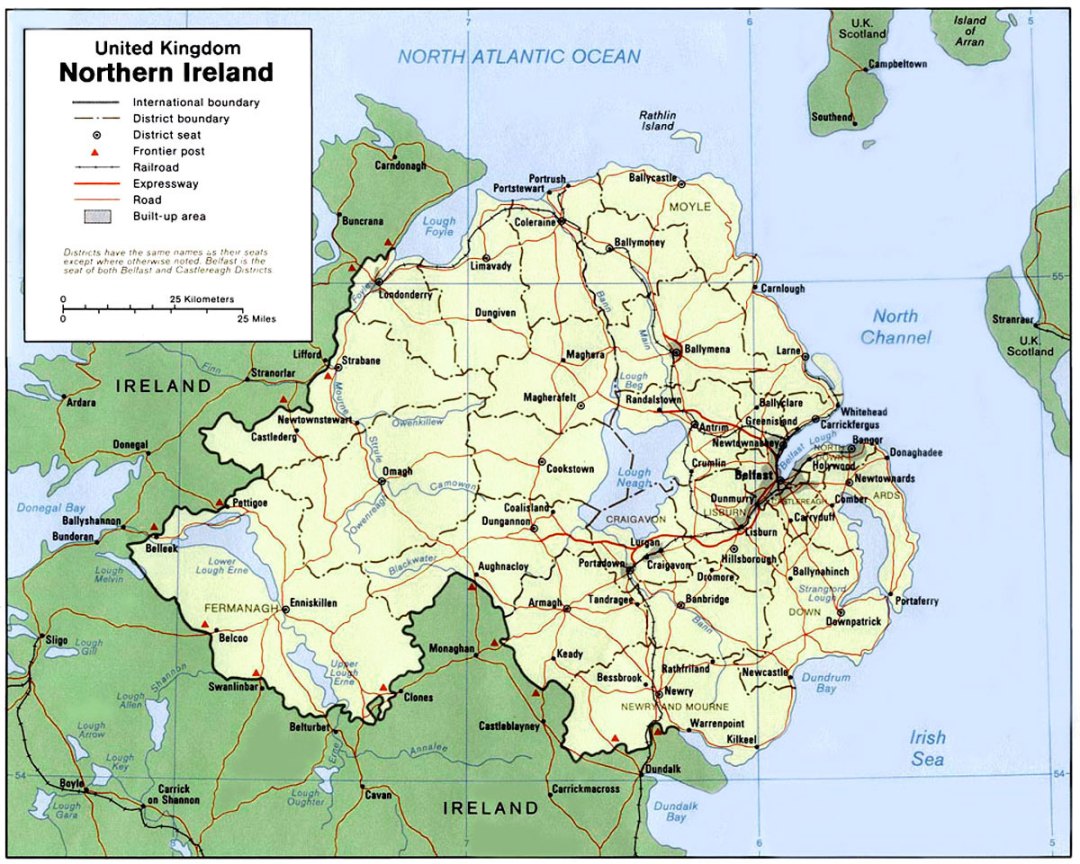

Northern Ireland – Coast is overall one of the more affluent of the 11 Local Council areas in NI, although there are deprived communities within it. The coastline is dotted with villages and towns as well as the communities inland, some in very rural settings. The mix of school types in NI-Coast is typical of NI as a whole.

The school system in Northern Ireland is complex and governance structures reflect the history and religious identity of different communities, within the oversight of the Department of Education Northern Ireland (DENI). The employer for staff in Catholic maintained, primary and post-primary (secondary) schools is the Council for Catholic Maintained Schools (CCMS). In Controlled schools the employer is an NI Department for Education body, the Education Authority (EA). Other types of schools include Integrated and a small number of Irish Medium schools. There is a selective grammar school system in NI and some grammars are Controlled and many Voluntary (independent charities).

The EA has formal oversight for the improvement of all schools, but other bodies exist to offer specific support to types of schools, for example, the National Council for Integrated Education (NICIE), the Controlled Schools Support Council (CSSC), and Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta (CnaG) which encourages and promotes Irish-medium education.

In NI-Coast we spoke to 22 leaders in total. This included leaders from controlled, maintained and integrated schools, from voluntary and controlled Grammar schools and from primary and post-primary (secondary) schools. We spoke to some leaders who had an overview of the area, and both principals and vice principals in schools.

What we were hearing

Commitment to school, place and community

Almost everyone we spoke to talked explicitly about their connection with NI, and often specifically with NI-Coast. For many, the connection played a clear role in career choices and progression. Several interviewees were ‘born and bred’ in the area. One had consciously chosen to apply to become Principal of the school they themselves attended as a child – others had moved to Coast from elsewhere in the province, often to take up a promotion. There were several accounts of careers that started in England followed by a ‘return’ to NI, usually for the draw of family or a spouse.

We were also struck that principals in NI-Coast were very invested in relationships with staff and communities which was often spoken of ahead of academic achievement and progression which were nevertheless taken very seriously and spoken of with pride. We heard stories of English principals with, it was suggested, a slightly different mindset, who had not been successful when they took up posts in NI.

All the headteachers and senior staff in schools we spoke to were consistently motivated by making a difference for children, communities and staff. We asked them what they were most proud of in their role and this was invariably an area in which they had been able to exert leadership and develop the school or support staff/pupils in some way.

Pressures

We were left in no doubt that headteachers felt under considerable and in some cases potentially unsustainable pressure. Factors that contributed to the pressure and mentioned consistently were i) a long running industrial dispute, ‘action short of strike’ (ASOS), by teachers; ii) what was variously referred to as ‘our broken system’ or ‘our crumbling system’; iii) lack of funding and over-supply of school places; iv) issues with a minority of parents; and v) the long-run impact of the pandemic.

The industrial dispute has continued over several years and varied between schools in how it had affected them, but most interviewees gave a sense that the constant negotiation with staff was energy-sapping, while many worried about the impact on school cultures and the expectations and experiences of teachers and emerging leaders.

The ‘broken system’ referred specifically to support services schools needed to function such as HR, Finance or legal support. The support services also included organisation and provision of specialist placements for students with specific needs, also widely regarded as difficult to access or inadequate. The Education Agency (EA) responsible for the services was considered not to be functioning well as a whole, even though there was respect for individual staff members.

Most of our interviewees highlighted funding challenges. Several schools faced large and growing deficits but didn’t appear to have scope to tackle the issue (for example, by reducing staffing costs). The surplus of school places was particularly significant at primary level, with several schools facing falling rolls and those headteachers’ time was consumed by the various implications.

Several interviewees suggested that the expectations of some parents – invariably a small minority – of schools have increased and they have become more demanding in recent years. Letters from lawyers are no longer uncommon. Other parents express themselves more forcefully in person. These issues were acutely stressful for some principals. Several felt they needed to grow a ‘thicker skin’ but were struggling to do so.

We heard repeatedly about a difference, since the pandemic, in what more than one leader described as the resilience of both adults and young people. Examples were often everyday occurrences like reasons given for requests for additional time-off, non-participation in activities, or lateness.

For every one of our interviewees, some combination of the factors sketched out here meant they felt under pressure, for some it was extreme pressure. Although some leaders were more able to insulate themselves from the emotional toll than others, strikingly, all principals saw the role as one with a limited time span. ‘It’s a burn-out job’ was the assessment of one post-primary principal who was very up-beat, confident and enjoying their role. Another noted the impact on their health, while another reflected on the connection between the demands of the role and a broken marriage.

Sustaining leadership

There were differences between headteachers in how they spoke about the pressures and the extent to which they were able to manage and sustain their role. More experienced leaders we interviewed tended to be leading relatively large schools, in both primary and post-primary phases. For them, the combination of extended experience and an ability to share leadership across a larger team appeared to make the job do-able (at least in the short to medium term). Most of the leaders we spoke to talked about either a team or a single professional relationship which kept them going. Several of these relationships were internal to the school, for example between a Head and Deputy, or a Chair of Governors and Head. Others relied on networks of peers – we heard of two local heads networks; WhatsApp groups of principals of schools with a similar designation and smaller principal networks based on professional friendships and shared challenges.

Where to next?

These were the initial themes that struck us from our conversations in NI-Coast, although we will undertake much more in-depth analysis of the interviews over time. There were other themes, of course, whether touched on or taken for granted. We will return to these when we visit another locality in Northern Ireland (NI-Urban/ Rural), later in the year. As we write this, the Stormont Assembly has just been restored and will undoubtedly have an impact on some of the issues we were told about.

One thought on “Our first Locality Case Study: Northern Ireland – Coast”